Flashback a couple years ago. I was standing at the front desk of the gym and a woman that I’ve worked with before approached me and told me she hurt her knee a couple days ago. She was walking fine and didn’t have any other indications of injury (bandages, braces, crutches, etc.). I asked her what she meant and she said her knee was in pain. As she said that she pointed above her knee, to her quad.

I asked if she could point to where it’s most sore. She pointed to the quad again. I asked her if she did any lower body exercises 2 to 3 days ago and she said yes. For the first time in over 50 years of this woman’s life, she was experiencing delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and confused that with being injured.

Soreness is often felt by first time gym-goers and novices especially when they’re introduced to a novel stimuli like an exercise or rep range they haven’t done before. Some people think soreness is an indicator of a good workout, others (like the lady above) hardly ever feel it. So what’s the deal? Lucky for you, that’s exactly what this article is for.

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)

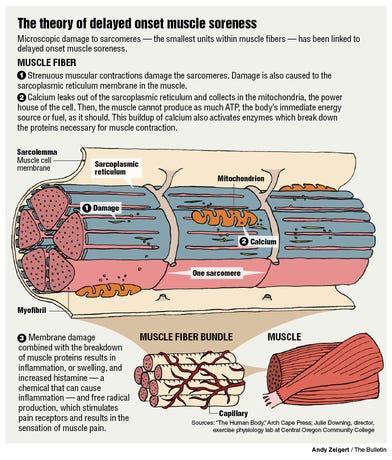

DOMS can be defined as muscle soreness experienced 24-72 hours after a workout. 12-24 hours post workout you’re unlikely to experience soreness and it will typically peak after 24-48 hours. DOMS is attributed to temporary muscle damage, inflammation, and histamine accumulation. Lactic acid is usually thrown around by sports coaches as a cause of soreness, but it doesn’t contribute directly to DOMS since lactate is cleared usually minutes after a workout is complete. TLDR; lactic acid doesn’t make you sore.

Eccentric muscle contractions (negative or lowering phase of the lift) are the primary culprit for DOMS. Lengthening muscles under load tends to induce more DOMS than just contracting a muscle concentrically (lifting phase, shortening under load). Eccentric contractions induce greater tension per unit of area due to lower motor unit recruitment. Damage to the muscle fibrils also makes sense as at least a partial mechanism for DOMS since there is a large concentration of pain receptors surrounding them. Muscle breakdown itself isn’t the only cause of DOMS since soreness doesn’t even appear until at least 12 hours after exercise

It’s hypothesized that there are secondary causes such as inflammation which slowly increases after the workout is completed. Acutely, exercise is harmful to the tissues and triggers an immune response to reduce reactive oxygen species and remove cellular debris. DOMS is therefore a sign that training caused enough of a physical and chemical disruption to elicit a healing response from the body. Generally, this is good. This means training was hard enough to stimulate change.

That being said, being devastatingly sore for 3 or more days isn’t a great idea and you may just be doing too much volume or under recovering.

What To Do When Your Muscles are Sore

Rest, Ice, compress, elevate. Just kidding. You’re not injured, your muscles are just sore and icing everything will give temporary relief at the expense of delaying the healing process by decreasing inflammation. Inflammation after all is a healing process, without it you would never recover from hard training. The best remedy I’ve found for excess soreness is movement. If your legs are sore hop on a bike for 10-20 minutes and circulate more blood through the area. This helps to shuttle nutrients to the muscles. Muscle contractions also help the lymphatic system drain excess fluid.

“But experts are now voicing concern over whether applying ice after an injury actually aids healing – or if, in fact, hinders it. American sports doctor Dr Gabe Mirkin coined the term 'RICE' in 1978. However, he backtracked on his initial hypothesis in 2015, writing that ice 'may delay healing, instead of helping'.”

Light band and body weight exercises can also be added to alleviate soreness. I still recommend training through soreness instead of taking a rest day but making the session more active recovery and not hammering yourself into a wall.

Use Soreness as a Guide

Soreness should be a guide for training. Anybody can make somebody sore, but that doesn’t mean anybody can write up or execute an effective workout. How sore you should be is highly goal dependent. In my opinion, DOMS is most useful to consider if the goal is muscle gain. Qualities like strength and speed are also skills that are highly dependent on enhanced nervous system function for improvement. These qualities don’t necessarily need constant DOMS to be effectively brought up. If you have general goals of just being healthy and ‘being in good shape’ then there’s little benefit to being overly sore and for long periods of time (greater than 3 days).

General rule of thumb, if you’re sore for 3 or more days, you probably did a bit too much. If you’re never sore, you probably aren’t ever doing enough. If the goals are speed (think running faster), strength (think squatting more), or skill (think becoming a better boxer) then soreness is a less reliable measure of whether you’re under-doing it but definitely still an indicator you could be doing too much or under recovering from your training. Although overtraining is possible, it’s usually a boogeyman. Don’t be afraid of training hard because of soreness. You learn to adjust your training over years but that means sometimes doing more or less to fine tune what works for you.